What is the Shariah?—the True Meaning

What is the Shariah?—the True Meaning

Excerpted From the Book: The Original Meaning of Ḥanafī Uṣūl al-Fiqh

Imran Ahsan Khan Nyazee

Related Links:

Photo by Adli Wahid on UnsplashLink to book excerpted from, The Original Meaning of Ḥanafī Uṣūl al-Fiqh

بِسْمِ اللَّهِ الرَّحْمَٰنِ الرَّحِيمِ

In the Name of God, Most Merciful and Compassionate,

and (with) prayers and blessings on Muḥammad and his

family.

Contents

- 1 Confusion About the Meaning of Sharī‘ah

- 2 The Sharī‘ah and the Qur’ān

- 3 Liability of Human Beings in General: The Covenant With the Creator

- 4 The Nature of the Covenant: The Obligations and the Demand for Performance

1 Confusion About the Meaning of Sharī‘ah

The first question a non-Muslim asks on hearing the word “sharī‘ah” (pronounced sha ree ‘ah,) is: what is the sharī’ah? This is a perfectly natural question. The correct answer, however, is not known even to ninety-nine percent, or more, of the Muslims. Those who attempt to answer cause more confusion than clarity. We will first note the typical answer very briefly for identification, without reproducing the various answers, as pursuing those answers is not the purpose here.

The favorite answer given to the Western audience by writers in the West, and by some scholars in the Muslim world, is that it is the law ordained by God. The answer is essentially correct, but these writers make additions to this answer that complicate matters. Thus, it is said that sharī‘ah is an ideal in the Qur’ān. What goes by the name of Islamic law or fiqh is the human version of the jurists’ interpretation of the sharī‘ah and it can differ from person to person and with the passage of time. In other words, this human version is in reality not God’s sharī‘ah, but what each jurist says it is.

It is also implied that the sharī‘ah is an unattainable ideal, that is, the interpretation of the texts is merely an attempt to reach this unattainable ideal. The question to be raised with respect to such an answer is: why would the Lord hold human beings liable for what is not in reality sharī‘ah, but a man-made version of it?

From another perspective, it is seen that the earlier jurists still exercise an authority over the people. To undo this authority, it is again suggested that the sharī‘ah is an unattainable ideal and what the people follow is merely a human interpretation. The sharī‘ah is permanent and infallible, while the human interpretation is subject to error and to change. Thus, there is nothing permanent about what the jurists have presented as fiqh or the interpreted version of the sharī‘ah. Further, one interpretation is the same as the other and over time the interpretation of jurists is likely to change. The main purpose is that the authority of the earlier jurists may be cast aside with ease and a new one may be preferred.

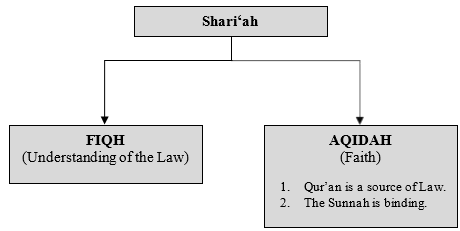

To answer the question about the meaning of sharī‘ah, we say: The sharī‘ah, in simple words, consists of two things: rules of conduct called fiqh (or the understanding of the rules of conduct) and the tenets of faith called aqīdah. Tenets of faith are important for understanding the meaning of sharī‘ah as there are certain things related to law that are based on faith. Thus, our belief (īmān) in the truth of the mission of the Prophet (pbuh) and that he (pbuh) is the Messenger of Allah, the One and only, gives rise to the belief that “the Qur’ān is a source of our laws.” This principle is a matter of faith and not understanding, as it cannot be proved by reason. The same applies to taqlīd of the Prophet (pbuh). As we believe that he (pbuh) is the Messenger of Allah, we must consider his commands and directives to be binding. This belief is affirmed in the Qur’ān on many occasions where the believers are asked to obey the Prophet (pbuh). There are some jurists who would add belief in consensus (ijmā‘) to this list, but we will not pursue this idea here. The following diagram explains what we have said so far.

It must be stated here that fiqh is exactly the same as the sharī‘ah insofar as the rules of conduct or law are concerned. The sharī‘ah is not some unreachable ideal existing in the texts alone. The Muslim jurists have answered this issue in two ways. The first is the position of the Ḥanafī School. The School maintains that where there are several conflicting answers about a rule of the sharī‘ah, only one of these answers is right. The Ḥanafi School believes that its version of fiqh consists of all the right answers, that is, the answers it has given are exactly the same as those intended by the Almighty in the texts. This explanation is based on the issue in uṣūl whether each mujtahid (jurist) is right or only one has the right answer. The Ḥanafīs believe that there is only one right answer. A tradition related to the issue is that one who makes a mistake gets one reward for trying, while he who is right gets two. A similar issue has been raised by Ronald Dworkin for law that there is only one right answer.

As compared to the position of the Ḥanafī School, most other schools, especially jurists like Imām al-Ghazālī believe that every mujtahid is right, thus the version of fiqh of each school is right and is exactly the same as the sharī‘ah law intended by the Lawgiver in the texts. The argument is something like this: The version of fiqh or opinions are like the different colors in the universe. As they are all made by God, they are all acceptable to Him, and one is not preferred over the other. Thus, the response of the jurists is that each mujtahid is right, and you are on the right course whichever view you follow. We may add here that this approach has also led to moving between schools, that is, the practice of “pick and choose.” Ibn Nujaym, the Ḥanafi jurist, has recorded a statement saying: “If you move from the Ḥanafī School to another school that is fine, but if you come back we will give you ta‘zīr (physical punishment) for going to a low-grade school and then coming back.” This should clarify the issue.

There is yet another issue that will be answered fully in a companion volume to this book. The issue is whether the impact of the sharī‘ah is confined to what is expressly in the texts or does it extend to our entire life, that is, does the sharī‘ah represent a complete code of life or does it cover a small part alone, leaving the rest to human reason? The answer is that the jurists unanimously believe that it covers our entire life. The explanation will be provided in the companion book.

We may now turn to the meaning of sharī‘ah in the technical sense, the meaning of sources of law, and the meaning of the discipline of uṣūl al-fiqh as seen by the Ḥanafī School.

2 The Sharī‘ah and the Qur’ān

ثُمَّ جَعَلْنَٰكَ عَلَىٰ شَرِيعَةٍ مِّنَ ٱلْأَمْرِ فَٱتَّبِعْهَا وَلَا تَتَّبِعْ أَهْوَآءَ ٱلَّذِينَ لَا يَعْلَمُونَ ((45:18))

إِنَّهُمْ لَن يُغْنُوا۟ عَنكَ مِنَ ٱللَّهِ شَيْـًٔا ۚ وَإِنَّ ٱلظَّٰلِمِينَ بَعْضُهُمْ أَوْلِيَآءُ بَعْضٍ ۖ وَٱللَّهُ وَلِىُّ ٱلْمُتَّقِينَ ((45:19))

هَٰذَا بَصَٰٓئِرُ لِلنَّاسِ وَهُدًى وَرَحْمَةٌ لِّقَوْمٍ يُوقِنُونَ ((45:20))

أَمْ حَسِبَ ٱلَّذِينَ ٱجْتَرَحُوا۟ ٱلسَّيِّـَٔاتِ أَن نَّجْعَلَهُمْ كَٱلَّذِينَ ءَامَنُوا۟ وَعَمِلُوا۟ ٱلصَّٰلِحَٰتِ سَوَآءً مَّحْيَاهُمْ وَمَمَاتُهُمْ ۚ سَآءَ مَا يَحْكُمُونَ ((45:21))

وَخَلَقَ ٱللَّهُ ٱلسَّمَٰوَٰتِ وَٱلْأَرْضَ بِٱلْحَقِّ وَلِتُجْزَىٰ كُلُّ نَفْسٍۭ بِمَا كَسَبَتْ وَهُمْ لَا يُظْلَمُونَ ((45:22))

And after (all) that We have now established you upon the AUTHORITATIVE SHARI‘AH: SO FOLLOW IT, AND FOLLOW NOT THE WHIMS OF THE IGNORANT. The protection of the ignorant will not bring you any gain in the sight of Allah: it is only the unjust that seek protection of the unjust, one from the other: but it is Allah who is the Protector of the Righteous. These are clear evidences (guidelines of the laws) for the people, and a Guidance and Mercy for a Nation with sound Faith. What! Do those who earn evil think that We shall deem them equal to those who believe and do righteous deeds, and that their life and death will be the same? Ill is the judgment that they make. Allah created the heavens and the earth with justice, so that each person may be granted the recompense of what the person has earned, with none being wronged in the least.

The Almighty says that now you have been chosen and established upon the noble and authoritative Shari‘ah. It is a body of laws that will bring you all the good things of life (as was the case with the Isra’ilis and as happened in history for the earlier sincere Muslims) if you follow it with sincerity. Do not follow the laws made by the ignorant preferring them over the Shari‘ah, for these ignorant people are unjust. It is the unjust who follow the unjust, so do not seek their protection. These instructions about following the Shari‘ah and repelling the ignorant unjust are a guidance for people who have sound faith.

And, says the Almighty, do not think that it will not matter if you do not follow these guidelines and instructions, and that your life will be the same as that of the sincere, even if you follow the unjust and seek their protection; your fate will not be the same, so don’t be deluded. The reason is that Allah has created the heavens and the earth with justice, and each person will be granted the recompense of what the person has earned, with none being wronged in the least. May the Almighty in His infinite mercy pardon us.

وَنَزَّلْنَا عَلَيْكَ ٱلْكِتَٰبَ تِبْيَٰنًا لِّكُلِّ شَىْءٍ وَهُدًى وَرَحْمَةً وَبُشْرَىٰ لِلْمُسْلِمِينَ ((16:89))

“And We have sent down to thee the Book explaining all things—a Guide, a Mercy, and Good News for Muslims.”

إِنَّ ٱللَّهَ يَأْمُرُ بِٱلْعَدْلِ وَٱلْإِحْسَٰنِ وَإِيتَآئِ ذِى ٱلْقُرْبَىٰ وَيَنْهَىٰ عَنِ ٱلْفَحْشَآءِ وَٱلْمُنكَرِ وَٱلْبَغْىِ ۚ يَعِظُكُمْ لَعَلَّكُمْ تَذَكَّرُونَ ((16:90))

“Allah commands justice and compassion, and giving to kith and kin; He forbids all indecent and contemptible deeds, as well as rebellion: He warns you so that you may constantly recall.”

The addressee here is the nation, the Muslim Ummah. Allah demands the enforcement of justice. Justice can only be enforced by the implementation of the Sharī‘ah. Justice, however, must be tempered with compassion, for it is concern for the human being that completes justice. The Islamic form of justice must shun all indecent and contemptible acts during its enforcement. Justice is not only corrective justice, but distributive justice too, and that requires the taking care of those around you and your relations. Rebellion against these lofty principles is not to be tolerated, therefore, no one should attempt to wreck the system of Islamic justice based on the shari‘ah. The Muslim Ummah must take these commands of the Almighty as a warning and constantly remind itself of its duty to do justice.

وَأَوْفُوا۟ بِعَهْدِ ٱللَّهِ إِذَا عَٰهَدتُّمْ وَلَا تَنقُضُوا۟ ٱلْأَيْمَٰنَ بَعْدَ تَوْكِيدِهَا وَقَدْ جَعَلْتُمُ ٱللَّهَ عَلَيْكُمْ كَفِيلًا ۚ إِنَّ ٱللَّهَ يَعْلَمُ مَا تَفْعَلُونَ ((16:91))

“Fulfill the Covenant of Allah, for you have entered into this Covenant. Do not break your oaths after ye have confirmed them (for this Covenant), for you have indeed made Allah your surety (seeking His support). Verily! Allah knows all that ye do.”

This is the Mighty Covenant of the Almighty that Man has entered into taking Allah as his surety.1 It cannot be broken as that will have dire consequences. Muslim jurists have written chapters on this Covenant, because it is the source of all liability in this life. It was offered to the mountains and even they refused to accept it despite their great strength and firmness, but Man accepted it, and he must now abide by it. This chapter has been devoted to the Noble Covenant.

وَلَا تَشْتَرُوا۟ بِعَهْدِ ٱللَّهِ ثَمَنًا قَلِيلًا ۚ إِنَّمَا عِندَ ٱللَّهِ هُوَ خَيْرٌ لَّكُمْ إِن كُنتُمْ تَعْلَمُونَ ((16:95))

“Do not sell the Covenant of Allah for a miserable price: for with Allah is (a prize) far better for you, if ye only knew.”

The Covenant of Allah is a priceless thing that will fetch you an even greater prize in the Hereafter and a good life in this world through the justice that you implement. Do not sell it for a miserable price. Stay firm and wait for the prize that will come in this world as well as in the next.

Allah Almighty demands justice from mankind and for this purpose he has laid down the sharī‘ah. The sharī‘ah is enforced through the Great covenant that Man has entered into, the Covenant of Allah. For the sake of justice then the sharī‘ah must reign supreme. The concepts embedded in these words are elaborated in this book. Here we may quote the great Imām al-Sarakhsī to see how he visualizes the idea of justice that is given in the Qur’ān.

The learned Imām, Shams al-A’immah wa Fakhr al-Islām, Abū Bakr Muḥammad ibn Abī Sahl al-Sarakhsī (God bless him) says in his book Adab al-Qāḍī: Know that adjudication based upon justice is among the strongest obligations, after īmān billāhi, and it is the most noble of the acts of worship. It is for this function that Allāh, the Exalted, associated the term khilāfah with Adam (pbuh), and said: “I will create a vicegerent on earth.”2 He established Dawūd (pbuh) and said, “O David! We did indeed make thee a vicegerent on earth: so judge thou between men in truth (and justice): nor follow thou the lust (of thy heart), for it will mislead thee from the Path of Allah: for those who wander astray from the Path of Allah, is a chastisement grievous, for that they forget the Day of Account.”3He commanded each prophet that He sent to do justice, until He sent the Seal of the Prophets (pbuh) and said, “It was We who revealed the Torah (to Moses): therein was guidance and light, and by its standard judge the Prophets.”4 And Allāh, the Exalted said, “Judge thou between them by what Allah hath revealed, and follow not their vain desires.”5 Imām al-Sarakhsī (God bless him) after quoting the verse, “Judge thou between them by what Allah hath revealed, and follow not their vain desires, but beware of them lest they beguile thee from any of that (teaching) which Allah hath sent down to thee,”6 says:

The reason is that a judgement based on the Truth is the manifestation of justice, and it is through justice that the heavens and the earth are maintained and injustice is removed. For justice calls out the reason of every reasonable man, the seeking of fairness (inṣāf) for the victim of injustice from the oppressor, the securing of the right for one to whom it belongs, and the commanding of the good and condemnation of the reprehensible. It is for justice that He sent the Prophets and the Messengers (God’s peace and blessings on them all), and it is with justice that the Khulafā’ Rāshidūn (God be pleased with them) were occupied.

The study of the above verses highlighted the requirement of justice, the ‘ahd (the Covenant) and the necessity of the shari‘ah for the enforcement of justice as demanded by the Covenant. In the remaining pages of this chapter, we will elaborate the meaning of the Covenant as the jurists understand it and show how it is linked to “every” human being. We will also see how the link between the Covenant and the human being translates into the aḥkām (rules). In other words, the relationship between the shari‘ah and the Covenant will be explained. This relationship will also highlight the legal position of non-Muslims with respect to the shari‘ah. The conclusion will be that whatever the system, political or social, the shari‘ah is supreme.

To elaborate this meaning, we will use some of our published writing. The published part is found in our book on Islamic legal maxims. The following three sections have been excerpted from this book, that is, Islamic Legal Maxims:

3 Liability of Human Beings in General: The Covenant With the Creator

A fundamental principle of the sharī‘ah, which indicates the source of all “human” liability and authority, is not a legal maxim derived by the jurists, but a noble verse of the noble Qur’ān. We will treat this verse as a qā‘idah here. This principle is discussed in uṣūl al-fiqh, but is also a primary rule for all fiqh. We may add here that the principle indicates all basic freedoms and restrictions, the nature of the social contract in Islam, the source for all political authority, and above all the sources of all human rights. It is, therefore, essential for the student of Islamic law to understand this primary principle. The principle creates the ahliyyat al-wujūb or the capacity for all rights and obligations. The principle is as follows:

وَكُلَّ إِنسَٰنٍ أَلْزَمْنَٰهُ طَٰٓئِرَهُۥ فِى عُنُقِهِۦ

Every human being’s obligations (rights and duties) We have fastened to his own neck (dhimmah).7

The word ṭā’ir is interpreted by the jurists as “liability” and the “obligation” imposed through causes (asbāb). The jurists also interpret this to mean the covenant made by each human being with his Creator. The covenant is also referred to as the “trust (amānah)”. We feel that the words “trust to be exercised by the people of Pakistan” in the Constitution should be understood in this meaning. The following verses indicate that the covenant is in the nature of an amānah (trust) and it is a favour from Allah bestowed on Man to the exclusion of all other creation. According to al-Dabbūsī, it is the rights of Allah that are the real amānah.

إِنَّا عَرَضْنَا ٱلْأَمَانَةَ عَلَى ٱلسَّمَٰوَٰتِ وَٱلْأَرْضِ وَٱلْجِبَالِ فَأَبَيْنَ أَن يَحْمِلْنَهَا وَأَشْفَقْنَ مِنْهَا وَحَمَلَهَا ٱلْإِنسَٰنُ ۖ إِنَّهُۥ كَانَ ظَلُومًا جَهُولًا ((33:72 ))

وَٱذْكُرُوا۟ نِعْمَةَ ٱللَّهِ عَلَيْكُمْ وَمِيثَٰقَهُ ٱلَّذِى وَاثَقَكُم بِهِۦٓ إِذْ قُلْتُمْ سَمِعْنَا وَأَطَعْنَا ۖ وَٱتَّقُوا۟ ٱللَّهَ ۚ إِنَّ ٱللَّهَ عَلِيمٌۢ بِذَاتِ ٱلصُّدُورِ ((5:7))

We did indeed offer the Trust to the Heavens and the Earth and the Mountains; but they refused to undertake it, being afraid thereof: but man undertook it; He was indeed unjust and foolish.

And call in remembrance the favor of Allah unto you, and His covenant, which He ratified with you, when ye said: “We hear and we obey”: And fear Allah, for Allah knoweth well the secrets of your hearts.

The words unjust and foolish in the above verse are meant to indicate the “will” by virtue of which man exercises a choice, something that only he has been granted as compared to the animal world. There are other special covenants mentioned in the Qur’ān, like the covenant with the Prophets, with Abraham, with the Banī Isrā‘īl.

4 The Nature of the Covenant: The Obligations and the Demand for Performance

Al-Dabbūsī builds an entire structure for the creation of the obligations for all mankind. He then removes certain persons from the demand for performance on the basis of excuses recognized by the sharī‘ah. The theory he built has not been appreciated by later jurists in all its details, although they were highly influenced by his ideas ….

- 1

- Most commentators interpret this to mean an oath, but others interpret it as a compact. See Muḥammad ibn Aḥmad ibn Abī Bakr al-Qurṭubī, al-Jāmi‘ li-Aḥkām al-Qur’ān 24 vols. (Beirut: Mu’assasat al-Risālah, 2006), 19:143.

- 2

- Qur’ān 2 : 30

- 3

- Qur’ān 38 : 26

- 4

- Qur’ān 5 : 44

- 5

- Qur’ān 5 : 49

- 6

- Qur’ān 5 : 49

- 7

- Qur’ān 17:13. The translators use the word “fate” instead of obligations, but that is not how the jurists interpret this verse. See verse 9:8 for the meaning of dhimmah. The word obligation is used in the wider sense here and not in the narrower sense of rights and duties created by parties among themselves.